Testing new treatments and vaccines can take years, if not decades, to gather enough data, so scientists are turning to a controversial approach that involves deliberately infecting volunteers with potentially deadly viruses, parasites and bacteria.

It was an unusual thing to volunteer for. But here they were – a group of young adults waiting to be attacked by mosquitoes carrying a parasite that kills more than 600,000 people every year.

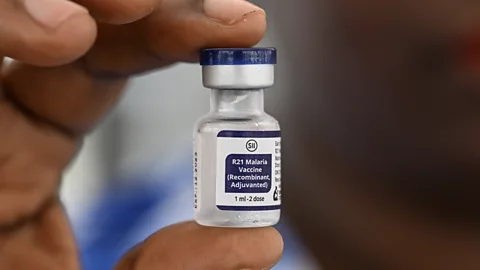

The group had agreed to take part in a medical trial at the University of Oxford’s Jenner Institute, to test a new vaccine against malaria. The vaccine – known as “R21” – and even in its early days, it was already generating excitement among scientists.

The trial took place in 2017, although the institute had been carrying out similar experiments with mosquitoes since 2001. Each volunteer was led into a laboratory. There, on a table, was a small pot, roughly the shape of a coffee cup, with a gauze cover on top. Inside were five buzzing mosquitoes, imported from North America, which had been infected with the malaria parasite. The volunteer would place their arm against the top of the pot so the mosquitoes could get to work, biting through the cover and into the volunteer’s skin. As the insects sucked their willing victim’s blood, the saliva the mosquitoes used to keep their meal from coagulating could carry the malaria parasite into the wound.

It is a colourful example of what is known as a “human challenge trial” – an experiment in which a volunteer is deliberately exposed to a disease. It may sound dangerous, perhaps even reckless, to knowingly expose a person to an infection that could make them seriously ill. But it is an approach that has become popular in recent decades in medical research. And it is one that is paying off, with some notable medical victories.

The R21 vaccine was later proved to be up to 80% effective at preventing malaria, and became the second malaria vaccine in history to be recommended for use by the World Health Organization (WHO). Recently, the first doses of the vaccine were given to babies in the Ivory Coast and South Sudan – both of which lose thousands of people each year to malaria.

And it was possible, in part at least scientists say, because of the volunteers who willingly pressed those mosquito-filled cups to their arms.

“Over the last 20 years there’s been a remarkable renaissance of challenge trials,” says Adrian Hill, professor of vaccinology and director of the Jenner Institute. “Challenge models have been used for everything from flu to Covid-19. That’s been really quite important.”

Now, scientists are looking to deliberately infect volunteers with more and more diseases – all in the hope of developing ever-more effective vaccines and treatments. Pathogens like Zika, typhoid, and cholera have already been used in challenge trials. Other viruses such as hepatitis C are being talked about as future candidates.

Although there is no central register of challenge trials, Hill estimates they have contributed to at least a dozen vaccines over the last two decades. One systematic review found 308 human challenge studies between 1980 and 2021 that had exposed participants to live pathogens.

Proponents believe the benefits of these studies firmly outweigh the risks, if conducted under the right settings. But some recent trials have pushed against the boundaries of medical ethics – and a handful of top scientists already feel uncomfortable about the speed with which the once-taboo experiments are now being rolled out.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt’s impossible to understand the lingering sense of unease that some have around challenge trials without going back to some of the darker moments of medical history. Most notorious are the experiments conducted by Nazi scientists, in which concentration camp prisoners were forcibly infected with tuberculosis and other pathogens. Less well-known are the actions of American doctors in Guatemala, who in the mid-1940s intentionally infected 1,308 people with syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

In the early 1970s, it emerged that doctors at Willowbrook State School in New York City had exposed more than 50 disabled children to hepatitis over the 1950s and 1960s, with the aim of creating a vaccine. Among medical researchers, “Willowbrook” has become a byword for shoddy research ethics. But the Willowbrook experiments also contributed to the discovery that there was more than one pathogen responsible for hepatitis.

Nevertheless, these examples all contributed to a backlash against the idea of intentionally infecting people with pathogens, says Daniel Sulmasy, director of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University, who was part of the US presidential commission that investigated the Guatemala syphilis trials. In the late 1960s and 1970s, scientists in high-income countries drew up collections of guidelines for medical trials that placed the wellbeing of volunteers as the foremost concern. The result was that challenge trials became far more difficult to conduct.

But gradually, as our approach to medical ethics becomes more nuanced, and in the face of a growing threat from pandemics, scientists are looking once again to human challenge trials.

Speed is a key motivation. In a traditional vaccine trial, volunteers are given either a vaccine or a placebo then asked to live as normal. The hope is that some volunteers will be exposed to the virus during the course of their day-to-day lives, offering a chance to test the vaccines effectiveness.

But it can be a cruelly slow process. A typical infectious disease vaccine can take more than 10 years to develop, with tens of millions of US dollars spent, while thousands – sometimes millions – of people continue to suffer from the disease.

Challenge trials cut to the chase. They eliminate the wait-and-see period by exposing a vaccinated volunteer to a virus directly.

“Time matters – sometimes we really need to be a lot faster,” says Andrea Cox, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. For her, the case for challenge trials is strong: they save time, money, and ultimately human lives. And they are particularly useful when dealing with rare pathogens like salmonella and shigella, she says, where a traditional trial might drag on for years as scientists have to wait for volunteers to come into contact with the disease by chance. “That’s not something that happens commonly, and so waiting for that to happen takes a very long time,” she says.

When done correctly, challenge trials can also act as early warning systems, scientists say. They allow researchers to be nimble, testing the vaccine in different types of people and highlighting any potential pitfalls in a vaccine’s chemistry.

Indeed, Cox says that vaccines occasionally have teething problems when first released – and it’s much better to find out about these issues in the comfort of a scientist’s lab, where treatments are readily available. She points to the Dengvaxia vaccine, rolled out by the Philippine government from 2016 to protect against dengue fever, the mosquito-borne virus that kills thousands each year.

The vaccine was given to 800,000 children in the Philippines. But researchers spotted a problem: whilst the vaccine worked well for children who had already suffered from dengue, it was potentially dangerous for children who had not previously been infected. In 2017, the World Health Organization changed its guidelines, recommending Dengvaxia not be administered to individuals who have not been previously infected with wild dengue virus.

This is exactly the sort of alarming detail that a challenge study might have highlighted early on, Cox says. Had Dengvaxia first been tested in a challenge trial, she says, researchers could have looked at how the vaccine and virus interacted within the bodies of various patients – including those who had already been infected with dengue, and those who hadn’t.

“Learning that a vaccine causes problems in a setting where there’s intense observation and medical care available is better than learning that in an area of the world where there are limited resources,” Cox says.

When debating challenge trials, scientists have long talked about the need for a reliable treatment in case things go wrong. The Jenner Institute started intentionally exposing people to malaria in 2001, by which point there were already effective anti-malarial treatments for the disease. And researchers at the institute are careful to use a strain of malaria that is highly sensitive to drug treatment, due to growing drug resistance in the parasite in many parts of the world.

But some scientists worry the ethical red lines become blurry once diseases without available treatments start to be used.

In 2022, researchers in the US gave two strains of the Zika virus to 20 healthy women, none of whom were pregnant or lactating as part of a trial that will also see a similar number of men infected with the virus. Zika causes mild symptoms in most adults but can trigger birth abnormalities in babies born to parents infected during pregnancy. In rare cases, it is also linked to neurological problems in adults. There is no treatment for the virus. The women were tested for pregnancy several times before the trial and asked to use birth control for two months afterwards. Although the results have yet to be published, all the women who received the virus infected, with most developing symptoms including a rash and joint pain during a quarantine period, according to details reported at a medical conference in 2023.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe study could provide a template for a larger Zika challenge trial, according to its co-author, Anna Durbin, an infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The researchers are now recruiting for a trial that will test the how effective a Dengue vaccine is at protecting people when they are deliberately infected with the Zika virus.

Perhaps more controversially given the life-long consequences of the disease, challenge trials using HIV have also been discussed – albeit as a distant hypothetical.

More realistic, however, is the prospect of a challenge trial for hepatitis C – a virus that is normally, but not always, treatable. Chronic infections with the virus can cause cirrhosis, liver failure and death if left untreated.

Researchers at the University of Oxford, for example, have secured funding to test a potential vaccine against hepatitis C using a challenge trial. Cox is also proposing a challenge trial with the virus after her frustrating experience of launching a traditional hepatitis C vaccine trial in 2012. She says it took six years and ultimately failed – a disappointing and emotional process that saw millions of people around the world succumb to the disease in the meantime.

A challenge trial would be much speedier, she argues. She proposes recruiting fully informed adult volunteers, who would freely consent to take part but would also be paid for their time. After being vaccinated, they would be deliberately exposed to the virus and then monitored over several weeks or months. Those who don’t clear the virus would be given antivirals.

But even with rigorous safety checks, accidents happen. In 2012, one volunteer at the Jenner Institute failed to show up for his mandatory medical check-in, seven days after being infected with malaria, says Hill. He was not found for a week. The volunteer was ultimately fine, and the incident was reported to an ethics committee. But the consequences could have been far more serious.

And it is the speed at which challenge trials are being undertaken that leaves some scientists like Eleanor Riley, professor emeritus of infection and immunology at the UK’s University of Edinburgh, feeling uneasy. “For diseases that have the potential to cause very severe disease, and where we don’t have a drug that will stop that organism in its tracks, I think the… balance becomes much, much harder,” she says. “Where there is a risk that one in 1,000 people die [for example], you’ve got to convince me that you’ve got something you can’t learn any other way.”

The list of pathogens used will grow too – including some that are dangerous and untreatable

Other ethicists have fewer concerns. Arthur Caplan, professor of bioethics at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, thinks the idea that challenge trials should only be done with treatable diseases is a “muddled morality”.

“Altruism and trying to help others is a very legitimate reason to want to participate in research,” he says. He points to experiments carried out to aid space exploration. In these trials, volunteers are asked to lie on a backwards sloping bed that causes blood to flow towards their brain, to mimic the effects of microgravity. Often, volunteers receive few benefits for taking part in these trials, he says; they simply do it for the public good. “So, the precedent for using people in studies who volunteer to face risk without benefit is there,” he says.

All of these issues came to the fore in 2021, when Imperial College London announced the world’s first Covid-19 challenge study. It was met with excitement, particularly from 1DaySooner, a US-based advocacy group set up in March 2020 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic to push for more challenge trials and help with recruitment for them.

The study has provided valuable insights into why some people are able to avoid getting ill even when they have been infected. It revealed they have a localised immune response in the lining of their nose that prevents the virus from getting a foothold in their bodies.

But the study also created controversy. Covid-19 has no cure, and unpredictable long-term effects.

Thirty-six young adults were exposed to the virus via a liquid dropped into their nose and quarantined for 14 days at a London hospital. “We saw [volunteers] had a lot of virus replicating in their nose and throat, and they remained infectious for about 10 days,” says the study’s co-author, Anika Singanayagam, clinical lecturer at Imperial College London. It also helped to prove the accuracy of lateral flow tests – the easy-to-use, at-home Covid tests used routinely in many countries at the time.

Imperial College London/Thomas Angus

Imperial College London/Thomas AngusBut Sulmasy, of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University, thinks the Imperial human challenge study did not pass ethical muster. “Not a lot was learned from that that couldn’t have been learned from alternatives,” he says. “Covid was novel. They didn’t really know a lot about long-term consequences.” He points out that several Covid-19 vaccines had already been approved by the time the trial started – reducing the need to take a risk.

In a written statement, Imperial College London said that Remdesivir – the antiviral treatment that can reduce the risk of severe illness in Covid-19 patients – was available throughout the study for any volunteer who became more unwell than expected. “When the study was ethically approved we were already a year into the pandemic,” says a spokesperson. “By this time there was a lot of information about the disease in young healthy adults that showed very low risk of severe disease in this group.” They added that the study “provided a wealth of granular data on [Covid-19] infection that would not have been possible with other types of trial”.

Since then, other Covid-19 challenge trials have sprung up. Researchers at the Oxford Jenner Institute are currently enrolling patients in a trial that will deliberately infect volunteers who have been vaccinated against Covid-19 with the Omicron BA.5 subvariant. The aim is to understand more about how the vaccines interact with subvariants of the virus. Those taking part will be paid £4,935 ($6,400) for their time and travel expenses.

Sean Cousins

Sean CousinsSean Cousins, a 33-year-old delivery courier in Southampton, UK, was paid more than £11,000 ($14,280) for taking part in three challenge trials between 2014 and 2020. In two he was infected with influenza, while in the other, it was respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). But he says he would have signed up even without the money. “It was just something new to try. [I wanted] to give my time […] and just help mankind if I could,” he says.

Scientists agree on one thing: we are likely to see more challenge trials in the future, not fewer. The list of pathogens used will grow too – including some that are dangerous and untreatable. It leaves some scientists, like Sulmasy, with a difficult-to-shake feeling of anxiety. “I think we’re going to push the boundaries, and it’ll only stop when someone gets hurt,” he says.

But others foresee enormous medical opportunity. With the right controls in place, they say, challenge trials could bring faster and better vaccine development for diseases that have plagued humanity for centuries. – bbc.com