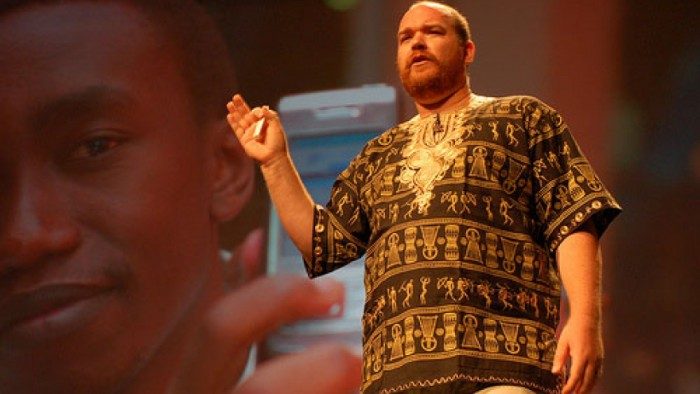

NAIROBI based Erik Hersman, an entrepreneur and technologist who is focused on advancing the use of technology as an empowerment tool in Africa, was recently in Harare to meet the local tech community.

Hersman, who is commonly known by the moniker, White African, had a lot of good things to say about Harare’s fledgling tech community. Even though there are still fewer early-stage tech enterprises, Hersman said: “Zimbabwe has a good nucleus on which to build a vibrant tech community.”

Viable startups in Zimbabwe do not exactly create novel products or services, but instead offer content, usually through blogs and social media, which they try to monetise through ads, media partnerships, and sponsorships. These include bootstrapped businesses like Techzim, 263 Chat, and Soccer 24.

While ICT access has been made easy by the ubiquitous home-grown mobile operator Econet Wireless, there is still no boon in software and application development by local startups. And Hersman is also of the view that “fewer Africans are involved in building hardware technology for the internet”.

It is in this vein that Hersman invented BRCK, a rugged WiFi internet device designed for use throughout the emerging markets, especially Africa. “We wanted a connectivity device that fit our needs, where electricity and internet connections are problematic both in urban and rural areas,” he said.

Currently, most routers and modems are built for New York and London, whereas most of the people connected to the internet today live in places like Harare or Nairobi. The BRCK was designed to work in harsh environments, where the infrastructure isn’t robust. The rugged design of the BRCK allows for drops, dust and weather resistance, and dirty voltage charging.

Hersman had a challenge for the young Zimbabwean techies and creatives. “Quit just talking. Innovate. Harare encounters a lot of problems everyday that you don’t get to solve when the solutions are easy to come by.”

Hersman was a co-founder of Ushahidi, a crowd-mapping digital platform that exposed Kenyan election killings in 2007. He explained that Ushahidi started out as “an ad hoc group of technologists and bloggers hammering out software in a couple of days, trying to figure out a way to gather more and better information about the post-election violence.” Ushahidi is now an acclaimed software worldwide used for “mapping crisis” in stressed environments.

In 2010 Hersman founded the iHub, Nairobi’s innovation hub for the technology community, bringing together entrepreneurs, hackers, designers and the investment community. This space is a tech community facility with a focus on young entrepreneurs, and to date has created 1 314 jobs, 152 companies and currently has 16 440 members.

But the situation in Harare remains stifling for young innovators and entrepreneurs. “You have to know someone who knows someone, or your father has to be somebody everyone knows,” said one local tech entrepreneur. And if it is not for patronage and pilferage, then it is the monopolistic tendencies of the big companies that are a big obstacle for young innovators.

“Incumbent and larger firms are hardly ever willing or able to partner with startups or to become customers, because they simply don’t trust upstarts or have convoluted hierarchies and decision making processes that don’t allow for collaborations with smaller players. The distrust is often mutual: more than once, entrepreneurs expressed that they were wary of companies like Econet simply copying their ideas following a partnership pitch” writes Nicolas Friederici, a fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute.

newsdesk@fingaz.co.zw