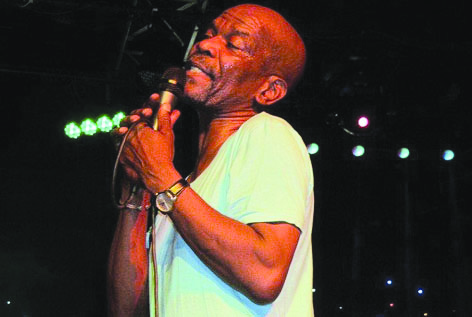

With a repertoire forged in apartheid South Africa, Stimela rose through the revolutionary flames and became musical titans who etched their names in world music posterity.  Ray Phiri and Stimela are legends. The apogee of their career would undoubtedly have to be the Graceland Tour with Paul Simon during the apartheid days in 1987. The tour was mired in controversy because of the then cultural boycott imposed on apartheid South Africa. But Stimela and other struggle icons in the mould of Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba seized the moment to blow the trumpet on the cruel practices of the disgraced fascist regime throughout the entire world. Today, singer/songwriter/guitarist and band leader Ray Phiri now 66 years old, is a respected musician worldwide. His hits such as Whispers in the Deep and albums such as People don’t talk let’s talk dealt the apartheid ogre some serious body blows. Beyond that however, the songs remain the sound track for post-apartheid South Africa besides generating income via royalties for the well preserved legendary band Stimela in their sunset years. In an interview with arts correspondent Admire Kudita, Ray talks about the business of music in South Africa as part of the country’s Department of Trade and Investment promotion recent trip to Zimbabwe in this first instalment of a lengthy interview .

Ray Phiri and Stimela are legends. The apogee of their career would undoubtedly have to be the Graceland Tour with Paul Simon during the apartheid days in 1987. The tour was mired in controversy because of the then cultural boycott imposed on apartheid South Africa. But Stimela and other struggle icons in the mould of Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba seized the moment to blow the trumpet on the cruel practices of the disgraced fascist regime throughout the entire world. Today, singer/songwriter/guitarist and band leader Ray Phiri now 66 years old, is a respected musician worldwide. His hits such as Whispers in the Deep and albums such as People don’t talk let’s talk dealt the apartheid ogre some serious body blows. Beyond that however, the songs remain the sound track for post-apartheid South Africa besides generating income via royalties for the well preserved legendary band Stimela in their sunset years. In an interview with arts correspondent Admire Kudita, Ray talks about the business of music in South Africa as part of the country’s Department of Trade and Investment promotion recent trip to Zimbabwe in this first instalment of a lengthy interview .

AK: How did your song Zwakala become the sound track of the much loved Zone 14? Ray Phiri: Tebogo Mahlatsi (also the originator of the famous Yizo Yizo series based on youth sub-culture in post-apartheid South Africa’s educational system) is the one that came up with the Zone 14 television series where it’s bringing in the life of the township, the clubs, the soccer players, hairdressing saloons, undertakers, the stokvels and including the stories surrounding the township, that there is a different soul to the township. He approached the recording company and requested Zwakala as a soundtrack for the show.

AK: Can we talk about remuneration for that song. How does that work?

Ray Phiri: There is publishing, there is needle time, and there is also the artistic performers’ royalties. So there are three revenue streams. Publishing is for the monitoring and the accounting, performance is for those who will be performing. Then there is composers’ royalties. So I get paid for all three: publishing because I wrote the song, performance because I performed on it and the composers, I get paid for needle time and for how many times we have to bring the series on.

AK: So how much do you get paid for the song in a year off the cuff?

Ray Phiri: Somewhere in the region of R300 000.

AK: What?

Ray Phiri: Yah. They are buying seconds. They bought only one minute of the song and they did what they wanted with it. They dissected it and edited it. They gave the song a new lease of life and all these young people who never knew the song got to be interested in the album. So it’s a win-win situation.

AK: It must be very gratifying for you as a writer as this is your intellectual property. What kind of right did they buy from you?

Ray Phiri: It’s called synching rights, synchronisation rights i.e. when you merge music with motion picture. It’s also one of the reasons why we are here in Zimbabwe. It is to try to add value to the trade and investment aspect of the creative industries here in Zimbabwe because the creative industries always suffer because of no recognition. It should be at the forefront because you look at Hollywood and Hollywood is arts business. Dancing is art, theatre is art, film is art and even sports is part of cultural business that a country can make a living out of.

AK: You have South African Music Rights Organisation (SAMRO). What is its role in the industry matrix?

Ray Phiri: It’s a collecting society. I have been a member of SAMRO since 1974 and am up for my pension now from them. All in all, as a collecting society they have upped their game because they are starting now to publish for those who do not have publishing and they have scholarships and bursaries to educate musicians especially songwriters. Because any industry that does not have human capital, that does not invest in human capital will not thrive.

AK: What does SAMRO do for the musicians in South Africa?

Ray Phiri: They are going further than that and collecting for most of Africa and are respected throughout the world as they are also affiliated to SESAC. Through the years of experience they have, they are now in a position to form the Performers Association of Southern Africa which monitors needle time. In South Africa, they now have been monitoring needle time through engaging with Independent Communication Authority of South Africa. In the past, regulation was cumbersome. It never explained what a performer was and what a record company is because once that is ironed out performers can get paid properly for needle time because the lines are drawn. The record company owns only the master (original recording from which CDs are printed) and not the intellectual property vested in the master. The composer’s right is protected in the intellectual property. We are getting our acts together. I don’t know whether it is being done here in Zimbabwe whereby every cd has to have an international standard record code number which helps track CDs anywhere in the world for purposes of remunerating the rights owner wherever it’s played.

AK: To the best of my knowledge it’s mandatory for books.

Ray Phiri: It’s a little bit challenging that some of us have the information but we haven’t met some of the people handling the copyright issues or creative industries here in Zimbabwe to exchange information and see where we can help and maybe engage our governments about this important subject of intellectual property rights.

AK: Maybe this can be arranged through the Department of Trade and Investment properly for next year when you can return and have plenary discussions and workshops with artists and industry representatives to share information.

Ray Phiri: Indeed yes it’s important for those who are new to the industry to know the pitfalls and the opportunities. They don’t have to go through what we went through. Also we should not forget that there is a difference between a record industry and a music industry. A record industry is the business side of the music industry. But then the record industry can only be sustained by the music industry side whose requirements are the social space where the music is going to be played amongst others. We have to have managers, agents, lawyers etc. It’s now business to business and business to consumers cutting out the middle men. Like right now we have new challenges with the digital revolution. We have the telecommunications spectrum and we have to see how we can be part of that as an industry because the way music is consumed is changing. We should keep the arts in party political agendas and not polarise it. For example political parties must have in their manifestoes an arts and culture policy because we are talking about how to shape the soul of a nation and how do we foster the national identity.

Ray Phiri is not just a music legend. He is a cultural and social transformation actor whose social conscience continues to animate his life work. He is currently sitting on the board of the National Arts Council in South Africa representing his home province of Mpumalanga and is also establishing the Ray Phiri Arts Institute. Next week he will talk about working with Tuku (helping developing Tuku music), Paul Simon and personal life including the tragic death of his wife.