Price rises have seen the biggest jump since records began in 1997 as the economy continued to reopen.

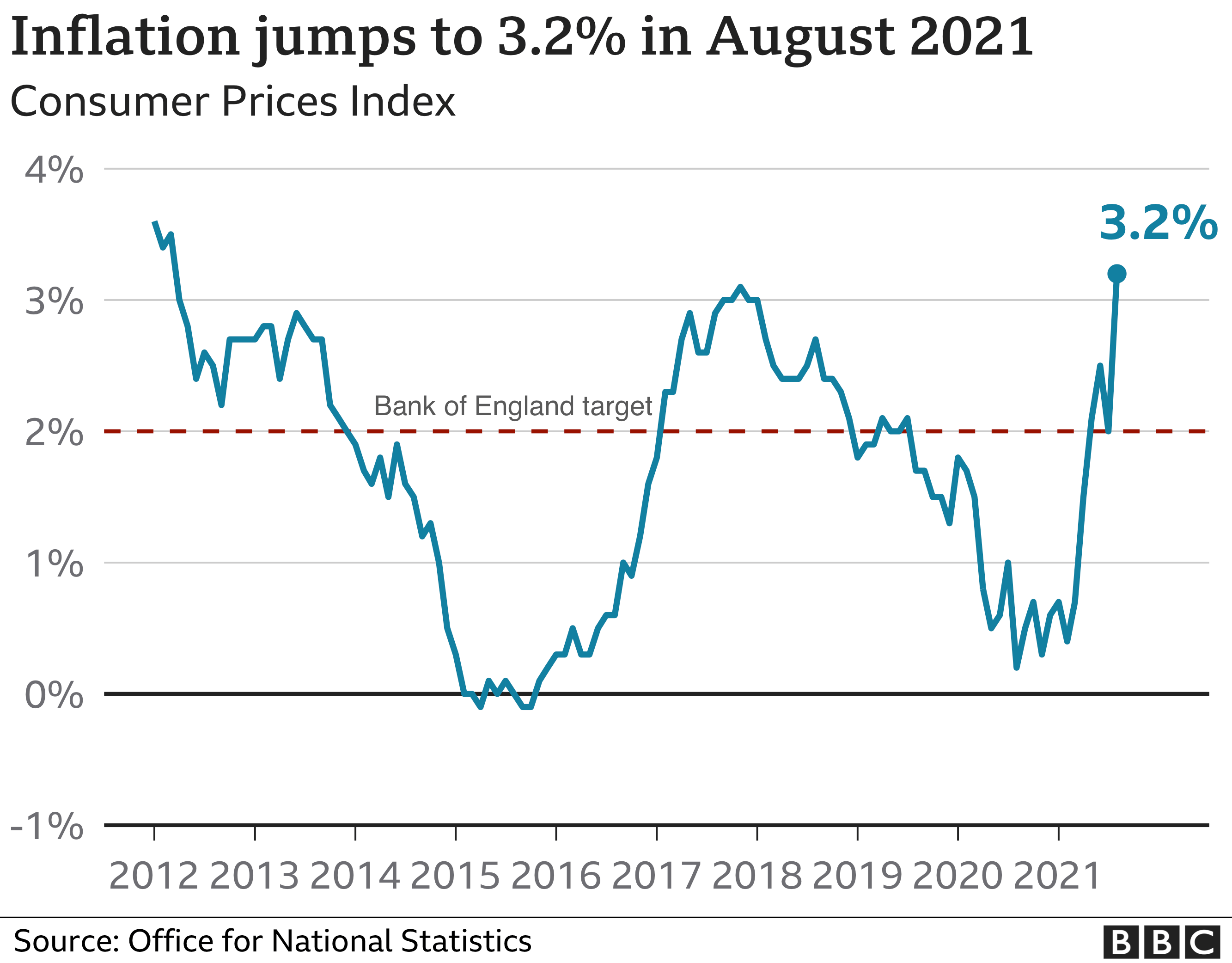

Official figures show that the increase in the cost of living, as measured by the Consumer Prices Index, hit 3.2% in the year to August.

Higher prices for food, petrol and used cars were all behind the spike, up from 2% the previous month.

The cost of living rose less rapidly in July because of lower clothing and footwear prices.

However, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) urged caution in reading too much into August’s price increases, which it described as “temporary”.

Eating and drinking out cost more last month in comparison with August last year, when the Eat Out to Help Out Scheme was running and diners got a state-backed 50% discount on meals up to £10 each on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

At the same time, business owners in the hospitality and tourism sectors received a VAT discount, designed to help some of the industries worst hit by the pandemic.

Jonathan Athow, deputy national statistician at the ONS, said: “August saw the largest rise in annual inflation month-on-month since the series was introduced almost a quarter of a century ago.

“However, much of this is likely to be temporary, as last year, restaurant and cafe prices fell substantially due to the Eat Out to Help Out scheme, while this year, prices rose.”

In August this year, transport costs also increased.

Average petrol prices stood at 134.6 pence a litre, compared with 113.1 pence a litre a year earlier, when travel was reduced under lockdown restrictions.

Used car prices were also partly to blame for price rises – they increased by 4.9% in just one month. Since April, they have gone up by more than 18% amid a shortage of new models.

Simply put, inflation is the rate at which prices are rising – if the cost of a £1 jar of jam rises by 5p, then jam inflation is 5%.

It applies to services too, like having your nails done or getting your car valeted.

You may not notice low levels of inflation from month to month, but in the long term, these price rises can have a big impact on how much you can buy with your money.

Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, told BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme that price rises seen in August were “almost unavoidable” because of the discounts available in 2020.

“Inflation, which is a year-on-year comparison, was always going to look strong compared to last year,” she said.

“Some of that rise reflected genuine factors too. In particular, we are now seeing the effects of higher global shipping costs and shortages of staff driving up food price inflation.”

She also expects, however, that the cost of living could continue to increase rapidly, with inflation exceeding 4% by November.

The latest official figures will add to the debate about whether interest rates need to go up to curb consumer spending and moderate prices.

Inflation now exceeds the Bank of England’s 2% target, aimed at keeping cost increases steady.

But Capital Economics points out that inflation is likely to fall back almost as sharply next year and that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is not expected to raise interest rates until 2023.

The central bank’s deputy governor, Ben Broadbent, insisted in July that it would not stop its efforts to boost the economy, despite the forecast of higher costs.

“While we know [inflation] is going to go further over the next few months, I’m not convinced that the current inflation in retail goods prices should in and of itself mean higher inflation 18 to 24 months ahead, the horizon more relevant for monetary policy,” he said.

Most of the inflation in goods prices was down to oil price rises and supply chain issues, he said, which was likely to “fall away” in the early part of 2022.

But given that Wednesday’s latest figures breach the Bank’s target, it must now write to Chancellor Rishi Sunak to explain what it will do to ensure that price prices are steady in future.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, added: “Higher inflation will inevitably raise questions for the Bank of England on the timing of tightening monetary policy and interest rate hikes to contain inflationary risks further down the line.”

She added: “However, any tightening now risks scuppering the recovery before it has a chance to take hold, so a delay until the middle of next year is likely.”

UK businesses are reporting difficulties in sourcing goods and recruiting staff because of disruption caused by the pandemic and problems such as HGV driver shortages, exacerbated by Brexit.

According to a survey of 2,000 people by Retail Economics, more than half of consumers are concerned about rising costs as a result.

The market research firm said on Wednesday that worries about the cost of living had reached their highest point in more than five years.

A record monthly spike in inflation, up to levels not seen for more than eight years, reflects a spluttering restart to the economy. Demand has rebounded, but the supply of goods and labour has not.

In August, there were one-off factors from the discounts and support measures last year.

As inflation is above 3%, the Bank of England governor has to write a letter to the chancellor explaining why. Stripping out the impact of Eat Out to Help Out last year would have meant this was not necessary.

This inflation number will go higher still in the coming months because of rising home energy bills. Alongside the rise in petrol prices and frankly incredible increase in used car prices, these inflationary pressures are becoming very visible.

The maths suggests that inflation could top 4% and then fall just as sharply, as long as there are no further economic shocks. Public perceptions matter significantly in regard to wage settlements for next year.

While the number is high and rising, this is still consistent with a “transitory” post-lockdown reopening inflation spike, predicted by the central bank.