Sony Music has cancelled the debts of thousands of artists who signed to the record label before the year 2000.

It means that many will now, for the first time, earn money when their songs are streamed on services like Spotify and Amazon Music.

Sony said it could not name the eligible acts due to confidentiality agreements, but a source said it would “include household names”.

It said some artists stood to receive “many thousands of dollars per year”.

I

IMusicians typically take on debt when they first sign to a record label. They are given a lump sum, known as an advance, to pay for recording studios, video shoots, distribution and other expenses. The money is then paid back when they sell their music.

However, many artists never earn enough to repay their advances, often because they get unfavourable royalty rates from their own record companies. Heritage black artists have been particularly affected.

And until the debt to their label is repaid, those artists are not eligible to receive income from streaming, and other royalty payments.

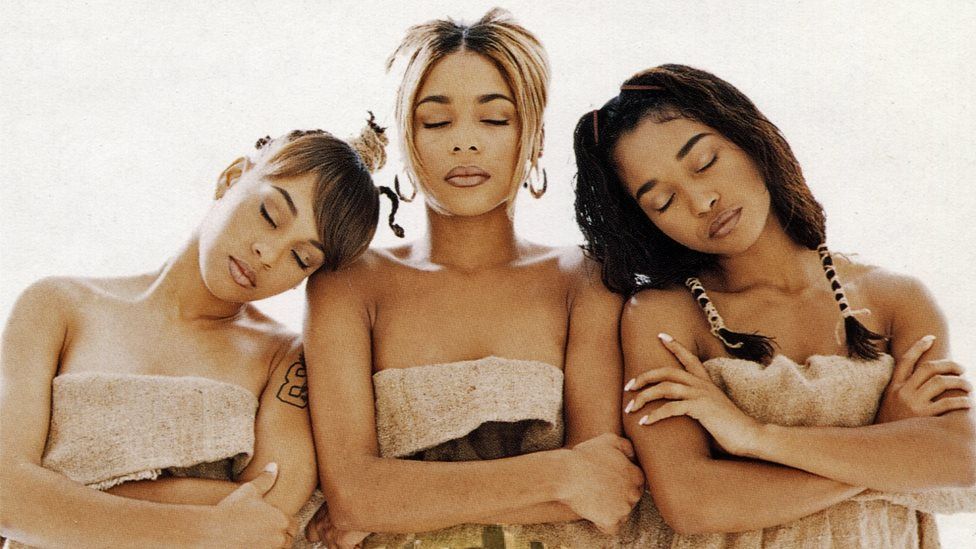

That’s how an act like TLC, who were signed to Sony subsidiary LaFace Records, ended up declaring bankruptcy in the 1990s.

The R&B stars declared debts of $3.5m, despite having one of the decade’s best selling albums, CrazySexyCool.

Sony’s announcement came in a letter to artists on Friday, a copy of which has been shared with the BBC.

“We are not modifying existing contracts, but choosing to pay through on existing unrecouped balances to increase the ability of those who qualify to receive more money from uses of their music,” it said.

In other words, the debt hasn’t been explicitly wiped out – but Sony will ignore it and pay royalties to affected acts, backdated to 1 January 2021.

Music industry lawyer Aurelia Butler-Ball said the scheme would “unlock” streaming revenues that artists were not previously entitled to, under contracts signed during the CD and cassette era.

“Many of the record deals [made] before 2000 didn’t recognise that streaming platforms would ever exist,” she said. “Therefore, artists didn’t have the right mechanisms in place to see those revenues.”

Sony’s initative comes amid mounting pressure on the record industry to be more transparent about the way it distributes money, particularly from streaming services.

A parliamentary inquiry is currently looking into the streaming economy, prompted by the vocal #BrokenRecord campaign, which seeks to address the imbalance in how profits are shared between record labels, musicians and the streaming services themselves.

Gomez musician Tom Gray, who founded the campaign, said Sony’s move was “incredibly welcome”.

“From the perspective of somebody who’s been running a campaign to try and get these companies to behave more ethically and transparently, it feels like a win,” he told the BBC.

Butler-Ball, who is a partner at Irwin Mitchell, said the initiative was something musicians had been “pushing for” for some time, but that it was only when the public began to take notice of the #BrokenRecord and #FixStreaming campaigns that record companies felt they had to act.

“I think this is absolutely a sign of labels recognising that there is pressure coming from not only artists but fan bases, and it’s increasingly being talked about publicly,” she said.

Sony is not the first company to take such a step. Indie label Beggars Group, which is home to acts like Grimes, Jarvis Cocker and The xx, has previously written off unrecouped balances on older contracts. However, Sony is the only major label to do so.

Its direct competitors, Universal and Warner Music, may feel they should follow suit – but Gray says they should go even further by fixing the low royalty rates given to artists in the 1960s and 70s.

“If that person’s on a 5% royalty, they’re not suddenly going to start earning lots of money,” he said, referring to the new deal.

“If you look at what labels like BMG are doing now, where they’re doing standard 30% deals [where artists gets 70% of the money], then Sony haven’t even got to what ‘good’ looked like a decade ago.”

Meanwhile, Sony’s move could enable heritage artists to sell their song catalogues to interested buyers – as Bob Dylan, Blondie and Barry Manilow have all recently done.

“There are plenty of funds out there looking to buy catalogues at multiple of 10 times and above [in exhange] for artist royalties,” music consultant Alasiter Moughan told the BBC.

“If an artist was unrecouped a potential buyer might want the artist to pay this balance back or not purchase the royalties at all, as no actual cash would be flowing through.

“This change in policy from Sony could be significant for an artist in this position.” – bbc.com