Interest rates are expected to rise again after figures revealed inflation remained at a stubbornly high level.

Inflation, which measures the pace prices rise at, was 8.7% in the year to May, the same rate it was in April.

Prices for flights and second-hand cars rising led to the unexpected figure, but the cost of food and energy is already hitting household budgets hard.

The Bank of England is expected to raise interest rates by 0.25% to 4.75% in a bid to reduce inflation.

But some economists have suggested the Bank could decide on Thursday to implement a more aggressive increase of 0.5%.

Part of the Bank’s job is to keep inflation at a target rate of 2% – far lower than the current rate of 8.7% and the markets have already priced in a interest rate hike.

The Bank has been steadily raising interest rates since the end of 2021, which make the cost of borrowing money more expensive, in response to consumer prices soaring.

This has led to concerns over loans, particularly mortgages, with homeowners – a third of adults in the UK – facing large increases in repayments when fixed-term deals come to an end. First-time buyers are also at risk of being priced out of the market as lending conditions become tighter.

The average two-year fixed rate mortgage on Wednesday hit 6.15%, while five-year deals were 5.79%.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said the government would support the Bank, which is an independent institution, as it “seeks to squeeze inflation out of our economy”.

He added that interest rate rises in other countries had led to inflation falling “over time”.

“That will happen here, but we need to be patient, we need to stick to the course, and then we will get to the other side,” Mr Hunt said.

Labour’s Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves blamed the Conservative government for failing to “get a grip” of inflation.

Karen Ward, a member of Mr Hunt’s economic advisory council and chief market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management, called for the Bank of England to “create a recession” to curb inflation, arguing that it had “been too hesitant” in its interest rate rises so far.

Ms Ward said there were signs a price-wage spiral was emerging, which is when wage rises help force prices up.

She said it was necessary for the Bank to “create uncertainty and frailty” in the economy to stop prices rising as fast.

“It’s only when companies feel nervous about the future that they will think ‘Well, maybe I won’t put through that price rise’, or workers, when they’re a little bit less confident about their job, think ‘Oh, I won’t push my boss for that higher pay,'” she told the BBC’s Today programme.

“It’s that weakness in activity which eventually gets rid of inflation,” she argued.

But Andrew Selley, chief executive of Bidfood UK, a wholesale food supplier said increasing interest rates was “not the right thing to do”.

“It’s stifling the economy. They need to look at other ways to support businesses so they can weather the storm,” he said.

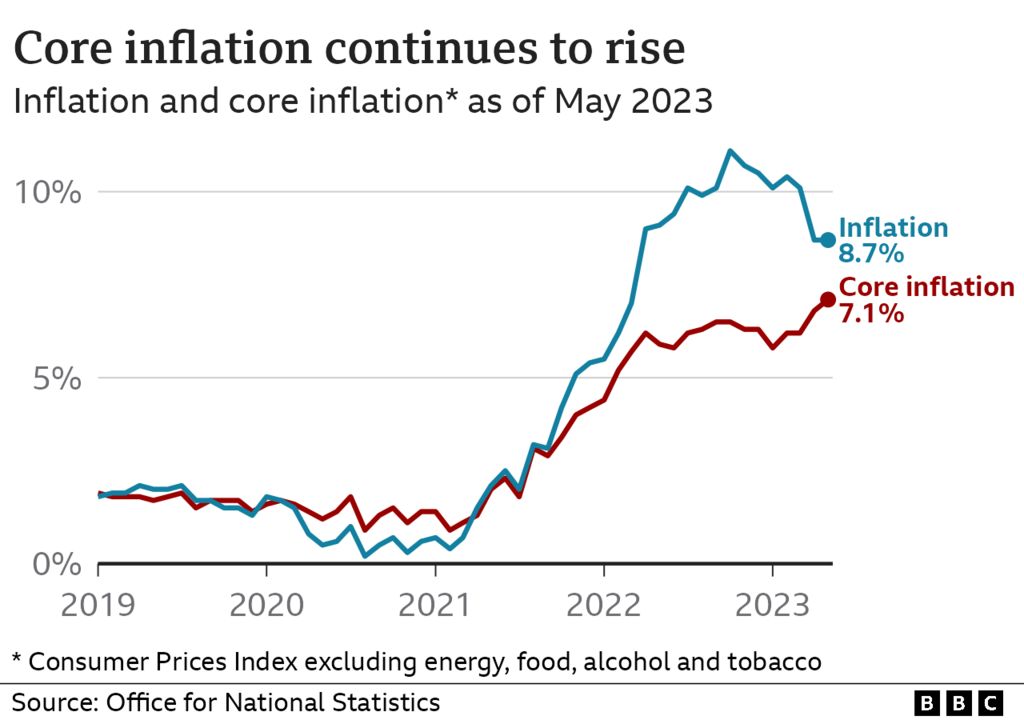

A key figure the Bank analyses when deciding on interest rates is so-called “core” inflation, which strips out direct energy and food prices, along with alcohol and tobacco.

Core inflation actually hit 7.1% in the 12 months to May, a jump from 6.8% in April, and is now at the highest level since March 1992.

Grant Fitzner, chief economist at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which produces figures on the UK economy, said core inflation rising was a cause for concern, with the increase being driven by rising service prices in cafes, restaurants and hotels.

“That’s probably driven, at least in part, by the increase we’ve seen in wages,” he added.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK, also said rising core inflation suggested firms might be passing on rising costs from higher wage bills to consumers,” she said.

UK wages have risen at their fastest rate in 20 years, excluding the pandemic, with regular pay excluding bonuses increasing by 7.2% in the three months to April.

But wages are still lagging behind the rate of inflation.

Inflation isn’t just stubborn, or sticky. In May, it was stuck at just below 9%, when really it should be falling by now.

International comparisons can be fraught, but they are instructive here, with the most directly comparable US inflation measure closer to 3%, and France and Germany closer to 6%.

The rise in core inflation is a shocker – this is the best insight into underlying inflationary pressures, excluding direct energy and food costs.

The Bank of England watch these figures very closely and there can be no doubt that they will rise again tomorrow, and probably again. We might even get some votes on the nine member committee for a larger rise tomorrow.

Pay failing to keep up with price rises has led to many households come under financial pressure in recent months.

Food price inflation, which is the rate at which prices for groceries have risen compared to the year before, was 18.3% in May, down slightly from 19% in April.

Sarah Coles, head of personal finance at Hargreaves Lansdown, said while food price inflation had eased, it was still at a level that “causes agony at the tills”.

“Costs have risen so far and so fast that we’re not going to see prices drop back to the level we were used to. In many cases we won’t actually see them fall at all: they’ll just get more expensive at a slower rate,” she said.

Separately, figures also released on Wednesday revealed that national debt was greater than the UK’s economic output for the first time since 1961. — bbc.com