The year 2039 might seem like a long way off, but Ian Crawford is already planning for it.

It will mark the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War Two – a big year for his employer, the Imperial War Museum.

Mr Crawford is chief information officer at the museum, and oversees a project to digitise its huge collection of pictures, audio and film.

With a collection of around 24,000 hours of film and video, and 11 million photographs, it’s a vast task.

And in the run-up to 2039, World War II material will be a priority.

Making digital copies of those historical sources is vital as the original copies degrade over time, and will, one day, be lost forever.

“When you’ve got the only copy, you want confidence that your storage system is reliable,” says Ian Crawford.

The amount of data needed for such long-term storage is growing all the time, as the latest scanners can record documents and films in great detail.

“It’s potential to grow is enormous really,” says Mr Crawford.

“We’re now looking at objects themselves and scanning in 3D – that can generate very large files.”

This deluge of data is not just hitting museums – it’s pouring down everywhere.

Businesses are buying more space for back-up data, hospitals need somewhere to store records, government needs a place to stash increasing amounts of information.

“We are continuing to create insane amounts of data,” says Simon Robinson, principal analyst at research firm Enterprise Strategy Group.

“For most organisations – it varies a lot – their data volume is doubling every four to five years. And in some industries it is growing much faster than that,” he says.

Data that needs to be held for a long time is not stored in traditional data centres, those vast warehouses, with racks of servers and blinking lights. Those operations are designed for data that needs to be accessed and updated frequently.

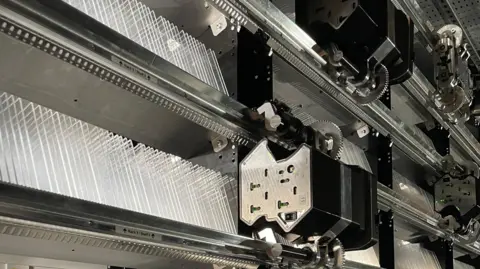

Instead, the most popular way to keep data for the long-term is on tape. In particular a format known as LTO (Linear Tape Open), the latest version being called LTO-9.

The tapes themselves are not unlike old VHS tapes, but a bit smaller and more square.

Inside the cassette is a kilometre of magnetic tape, capable of storing 18 terabytes of data.

That’s a lot – just one tape can hold the same amount of data as almost 300 standard smartphones.

The Imperial War Museum in Duxford uses a tape system from Spectra Logic. The machine, around the size of a large wardrobe, can hold up to 1,500 LTO tapes.

Such LTO systems dominate the market for long-term storage. They have been around for decades, and have proved themselves to be reliable.

It’s also pretty cheap, which is important as generally customers want to pay as little as possible for long-term storage.

HoloMem

HoloMemNevertheless some are convinced it can be done better.

In a former wallpaper factory in Chiswick, west London, a start-up firm has been developing a long-term storage system that uses lasers to burn tiny holograms into a light-sensitive polymer.

Chief executive Charlie Gale points out that with magnetic tape, data can only be stored on the surface, whereas holograms can store data in multiple layers.

“You can do things called multiplexing, whereby you can layer multiple sets of information in one space. That’s really kind of the superpower of what we’re doing. And we believe we can put more information in less space than ever before,” he says.

HoloMem’s polymer blocks can handle extreme temperatures, without the data becoming corrupted – between -14C to 160C.

By comparison, magnetic tape needs to be kept between 16C and 25C, which means significant heating and cooling costs, particularly in countries with extreme temperatures.

Tape also needs replacing after around 15 years, whereas the polymer is good for at least 50 years.

Mr Gale notes that, as the laser chemically changes the polymer, the data can’t be tampered with, once it has been written.

Holomem’s prototype system, which will be able to store and retrieve data, will be ready later this year.

Mr Gale says the cost of the system has been kept down by using standard, widely available components, including the laser – so, he’s confident that HoloMem will be able to match, or beat the costs of magnetic tape.

HoloMem will need to be competitive, as looming over the market is a formidable competitor.

Through its research arm, Microsoft is developing its own long-term data storage system.

Like HoloMem it has decided that it’s time to move on from magnetic tape, but Microsoft has chosen glass as it storage material.

Called Project Silica, the system uses powerful lasers to create tiny structural changes in the glass, called voxels that can be used to store data. The voxels are incredibly small and can be packed into layers.

Microsoft says that a 2mm thick piece of glass about the size of a DVD would be able to store more than seven terabytes of data.

The system stores the glass panes on racks, where they can be accessed by small crab-like robots that zip along rails.

Cheap and durable, glass is an attractive storage medium says Richard Black, who heads up Project Silica.

“It’s pretty much immune to temperature, humidity, particulates, electromagnetic fields,” says Mr Black.

It could potentially preserve data for hundreds and perhaps thousands of years.

Such a system could, one day, be integrated into Microsoft’s huge cloud computing business, Azure.

But that is some way off as the system has years of development ahead of it.

Back in Duxford, the Imperial War Museum, like many organisations, has been experimenting with artificial intelligence. They recently tested whether AI could identify different models of Spitfire in pictures from its image catalogue.

Mr Crawford thinks that AI could be incredibly useful in cataloguing its digital library, work that would take humans hundreds of years.

The ability of AI to trawl through vast amounts of data has made keeping that data even more important – there could be something valuable lurking there.

“In the past business was archiving data just in case they needed it. Now there’s an actual business reason why they might want to go back and do some analytics,” says Mr Robinson.