ZIMBABWE’S plans to import coins from the United States to alleviate the shortage of coins for small denomination change has collapsed, meaning the country will continue to depend on South African rand coins in a predominantly US dollar economy. A Ministry of Finance senior official, Eria Hamandishe, said the plan came off the rails because of Zimbabwe’s sour relations with the US.

ZIMBABWE’S plans to import coins from the United States to alleviate the shortage of coins for small denomination change has collapsed, meaning the country will continue to depend on South African rand coins in a predominantly US dollar economy. A Ministry of Finance senior official, Eria Hamandishe, said the plan came off the rails because of Zimbabwe’s sour relations with the US.

“As things stand, I can say that deal is off,” Hamandishe told delegates at a recent Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce Economic Symposium. “During the negotiations, at one time we appeared to be agreeable, then (at) the next meeting, the atmosphere was different. We (had) thought we were making progress,” he said.

“I think it had something to do with the sanctions,” Hamandishe suggested.

The US imposed economic sanctions against Zimbabwe through the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001, restricting access to financing, debt relief and rescheduling, forcing President Robert Mugabe’s government to operate on a cash only basis. The sanctions, together with those imposed by the European Union, resulted in the country’s economy sliding into an unprecedented economic crisis, characterised by hyperinflation, which eventually forced Zimbabwe to abandon its own currency in 2009 in favour of a multi-currency regime anchored around the US dollar.

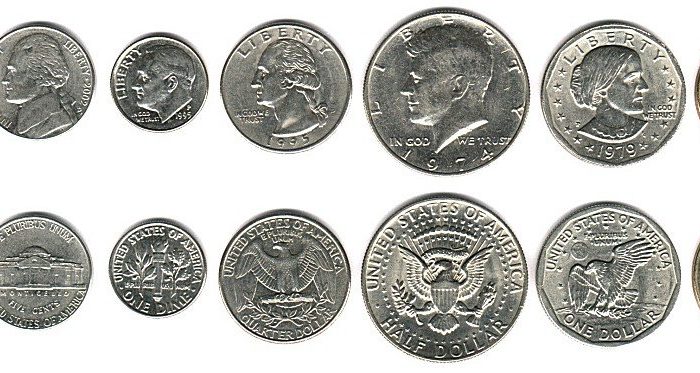

But use of the multiple currencies has had its own challenges, including shortages of small denomination coins for change in transactions. Hamandishe indicated that delegations from Zimbabwe had over the past three years travelled to America in the hope that the coins deal would materialise. On average, coins make up 13 percent of a nation’s currency and this is usually about 10 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to experts. At Zimbabwe’s current GDP of above US$10,8 billion, the value of circulating coins should be at US$180 million.

An economist explained the potential burden Zimbabwe was likely to grapple with if this deal had gone through: “To put this figure into context, 1 400 tonnes of coins needed to be shipped from the US to Zimbabwe. This is the equivalent of about 30 tonne trucks numbering 50. Additionally, more and more coins would need to be imported over time.” Before the elections last year, former finance minister Tendai Biti had said government was finalising importation of the coins from America. Biti hinted, at the time, that the US Federal Reserve had agreed to supply coins and replace soiled notes to Zimbabwean banks in a bid to end change problems in the economy.

Zimbabwe has been saddled with change problems since the introduction of multi-currencies in February 2009. Retailers had been offering consumers credit notes, tokens, bubble gums or sweets to settle small change. Hamandishe said with increased circulation of coins from South Africa, the availability of change in small denominations had improved. “Had the situation not improved, the other option would have been to mint our own coins,” Hamandishe said.

Bankers had previously urged government to resort to this alternative. The Bankers Association of Zimbabwe made a proposal for the country to mint its own coins for change in 2012. According to the proposal, the coins were to be exchanged on a dollar-for-dollar basis, enabling people to redeem coins for notes should they accumulate large amounts of coins. While coin demand in Zimbabwe remains very high, some economic analyst say the arrangement, shipping and transportation costs to import foreign coins had discouraged local banks from even trying to carry out the exercise.

“It is nowhere close to being profitable. How did government intend to recoup the cost of importing and circulating coins in Zimbabwe?” asked one bank economist. In modern commerce, the purpose of coins is to make for efficient small value transactions. Banks do not derive much profit from providing coin services to the transacting public. Generally, the issuance of coins is only profitable to the issuer, usually the central bank.