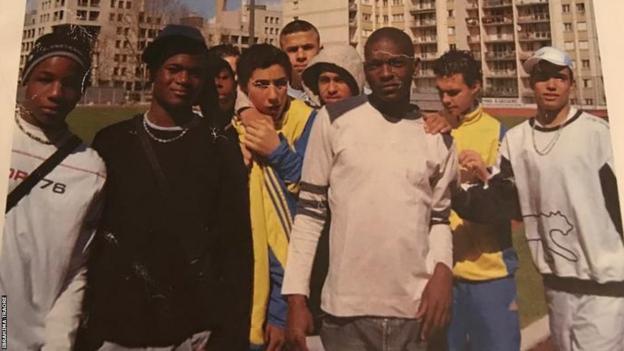

Ibrahima Traore smiles as he parks his black Range Rover outside the apartment block where his footballing story began.

He is back in Pantin, just outside the north-east corner of the peripherique – the ring road that separates central Paris from its suburbs.

Amid the din of sirens and the aroma of fast food, Traore buzzes in and takes the lift to the fifth floor. The doors open and his brother is waiting to welcome him back to their childhood home.

Inside, there are photos of the pair’s Guinean father and Lebanese mother, as well as shots of grandparents and younger generations of the family. Dominating the view through the floor-to-ceiling windows, across a dual carriageway and tramline, is a vast sports complex, with two 4G football pitches.

“That’s our Camp Nou, our Anfield,” Traore says. “We used to jump over the fence at seven in the morning to practise our free-kicks. Before school and after school, it was football. Only football.”

For many of the kids growing up here, constant practice can lead to the ultimate reward – a career in the professional game.

Traore, now 35, played more than 250 games for four different clubs in Germany’s Bundesliga and captained Guinea at the 2019 Africa Cup of Nations.

His inspiration growing up came from the success around him, rather than the television screen.

“I remember just across the street, we had the player who used to play for Manchester United: Gabriel Obertan,” says Traore. “It’s the dream from everyone and then even more when you have someone who comes from the same suburb who makes it.

“When you hear that it’s possible that, being from this area, you can play for a team like Manchester United, that is something that you want to follow, you want to pursue.”

As the clock strikes 4pm, children and coaches flood on to the pitches below. Aston Villa’s Moussa Diaby, former Arsenal winger Nicolas Pepe and France and Monaco defender Youssouf Fofana all started out at the same facility, which is shared by local clubs Esperance Paris 19eme and Solitaire Paris Est.

On the biggest stage of them all, Paris’ finest are everywhere.

Thirty players at the 2022 men’s World Cup in Qatar were born in the vicinity of France’s capital. Compare that to two other hotbeds of youth football: Sao Paulo provided 12 World Cup players and Greater London eight.

There were 11 Parisians in the France squad that lost to Argentina in the final, with the other 19 spread across eight national teams: Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal, Ghana, Cameroon, Portugal, Germany and Qatar.

And then you have the icons of the recent past. World Cup winners Thierry Henry, N’Golo Kante and Paul Pogba all grew up in the banlieues(suburbs) of the French capital, as did Kante’s former Leicester team-mate Riyad Mahrez.

How has Paris become a city that churns out more football talent than anywhere else?

Post-war immigration from football-loving former French colonies in north and west Africa is the obvious reason why Ile-de-France – as suburban Paris is known – is such a remarkable football factory.

Traore was born in Paris before moving to Guinea, settling back in the French capital from the age of four with his mother and siblings.

“You have a lot of people from North Africa round here; we used to say they are the real street footballers,” he adds.

“Then you have a lot of Senegalese, Guinean, Malian people round here. In the summer, we used to do an Africa Cup. All the Guinean players would be in one team. All the Malian players, they will be in one team. Ivory Coast… whatever you want. It’s crazy, because everyone is defending his country, and then it’s just insane.”

It was during one of these informal tournaments that a local scout spotted Traore and set him on the path of a professional career.

But that influx of talent and culture also emerged into an environment perfect for super-charging player development.

A local government policy of building high-quality football facilities in every Paris banlieue, partly to keep kids off the streets and out of trouble, has been fundamental to making the sport cheap and accessible to all.

“You come down from your building and you have a football field, so the first thing you do is go play football,” says Abdelaziz Kaddour, sports director of FC Montfermeil 93, a thriving club in Seine Saint-Denis, a suburban Paris region with one of the highest crime and unemployment rates in France.

Abdelaziz and Montfermeil oversaw the development of Arsenal defender William Saliba after he transferred from nearby AS Bondy, the club where France superstar Kylian Mbappe played as a child.

“Young people round here play football practically all day long,” says Abdelaziz.

“And on top of that, most of the pitches are small. That means, they touch the ball a lot. They learn to dribble. And over time, it gives them a lot of quality, dribbling, speed, seeing things before others, tackling, intensity.

“And what’s more, they want to make a living from football. They have the spirit. When you ask them the question, they want to be professional footballers at all costs.

“This is not an easy place to live. Many families are in difficulty. The children know it and give their all to succeed. It builds a mentality and that perhaps makes the difference, in addition to talent.”

Sebastien Bassong, the former Tottenham, Newcastle and Cameroon defender, began his passage to football stardom at Deuil Enghein, a club located in Val d’Oise, directly to the north of Paris. He says football is “in the DNA” of those who grow up in the banlieues.

“There’s a certain mindset that’s very contagious,” says Bassong. “I’ve got bigger brothers, so to make myself a name was difficult. But as soon as I started playing football, people started seeing me differently. I started to exist as soon as football came into my life. I started to puff my chest out a bit.”

Bassong’s talents were such that at the age of 13, he followed the path taken by Henry and Nicolas Anelka to Clairefontaine, the world-famous residential academy that has long cherry-picked the best talent from the Ile-de-France area.

“We call it the Harvard of football,” says Bassong. “Most of my football IQ came from Clairefontaine. You think football, you drink football, you smell football, you sleep with your ball and, above all, you learn discipline. They develop champions.”

Those not fortunate enough to be spotted by the scouts of Clairefontaine improve their skills in one of the biggest and most competitive amateur leagues in world football.

The Ligue de Paris Ile-de-France has more than 1,000 clubs and 270,000 players. It’s such an important organisation that it has an office in the picture-perfect Place Valois, a well-struck free-kick away from the Louvre museum, right in the heart of Paris.

“Some of the great French players, or players who play in the major European leagues, say that what served them best was training in the Ile-de-France, that the level was very, very good,” says the league’s president Jamel Sandjak, a former defender of Algerian descent who played in the league before moving into football administration.

“Most of the France national youth teams are full of our players. So our regional teams are playing at national level. Scouts from all over the world come to Ile-de-France to look at players in our leagues.”

The proliferation of foreign scouts explains the vast numbers of Parisian players who end up in the Premier League, with Liverpool’s Ibrahima Konate and Chelsea’s Axel Disasi among the latest batch. Konate even returned to his old Paris banlieue to unveil his Liverpool shirt, while a delirious crowd lit red flares and chanted his name.

English teams have benefited from the fact that Paris St-Germain, the one truly elite club in the Paris region, has long favoured spending on overseas galacticos over developing homegrown talent. This policy came back to bite them in their one and only Champions League final in 2020, when they lost 1-0 to Bayern Munich, the winner scored by Kingsley Coman, a player PSG had released on a free transfer to Juventus six years earlier.

Yves Gergaud, a former PSG youth coach who scouted Coman at the age of nine, says the then-18-year-old winger’s departure from the Qatari-owned club was prompted by the £33.5m arrival of Brazilian Lucas Moura to play in his position.

“It’s all about business,” says Gergaud.

“For 15 or 20 years now, they have wanted to win the Champions League, and they are trying to achieve that by attracting very great players, like Messi, like Neymar, like Thiago Silva.

“But unfortunately, they are still perhaps missing a little bit of soul.

“You have the academy in one corner, and the pro team in another corner, directors and managers changing all the time, so it’s very difficult to really develop players. But it’s true that you could field three or four teams of players from the Paris region in the Champions League.”

For their part, PSG owner Nasser Al-Khelaifi insists the era of “flashy bling-bling” is over and the club point to the emergence of 17-year-old midfielder Warren Zaire-Emery – now a starter for France as well as his club – as evidence that the academy and first team are more closely attuned. Gergaud is not convinced.

“I was at Paris St-Germain from 2002 to 2007 and people were already saying that at the time,” he adds.

“There is good work done in the academy. The scouts do a good job – they manage to detect very good young people but then it’s difficult to get them to the first team because they don’t have a reserve team and they find themselves being restricted to the under-19 championship.

“So there are players who can be ready like Warren Zaire-Emery at 16 or 17 years old, but there are others who should be able to keep developing at PSG and reach the first team.”

The concentration of young talent in one city and its suburbs has created something of a circus around Paris’ grassroots football.

Montfermeil sporting director Abdelaziz says there are often more scouts and agents than family members on the sidelines.

“When I started, I was scouting a lot in the Paris area but now it’s starting to be impossible,” says Jennifer Mendelewitsch, an agent from Supernova Management, based in the Bois de Boulogne in western Paris.

“There are too many agents, too many people are trying to find the kid, the boy, who’s going to make it. Right now, it’s the jungle to get a player in the Paris area.

“You speak to a family and they already have agents and the kid is only 12. It’s way too early. Let them be a kid. If they’re going to make it, they’re going to make it.”

Even as she delivers the words, Mendelewitsch knows she’s fighting a lost cause.

With Mbappe and Zaire-Emery at the head of an army of talent, the battle for the brightest stars in the city of lights is as fierce as any on the pitch. – bbc.com