Book Review by Diana Rodrigues

FORTY-five years ago, on April 18 1980, Isidore Mabasa and his cousin Owen set out from their home in Chitungwiza’s Unit K, making their way to Chinembiri Primary School.

En route they saw that St Aidan’s School had been taken over by groups of people singing and dancing, while others were handing out Zanu-PF T-shirts and paper caps.

An ecstatic senior citizen was running up and down the road flapping his hands and crowing, pausing now and then to call out ‘Pamberi neJongwe!’. When the boys finally got to school, they were sent back home, because it was Independence Day.

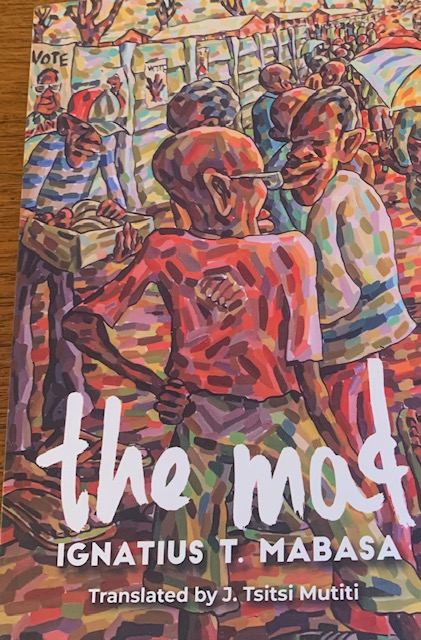

Nineteen years later, College Press would publish Isidore Mabasa’s first novel, Mapenzi, a classic Shona-language novel describing the first decade of post-independence Zimbabwe. ‘Inspiration chooses its own language ― I write in Shona ― it’s who I am’, Dr Mabasa told me in a recent interview. Mapenzi was praised in 1999 by the Times Literary Supplement as a ‘literary discovery’, but it is only recently ― thanks to a translation by J. Tsitsi Mutisi ― that English-language speakers can read about the challenges for many Zimbabweans, brought by change in the years following 1980.

Published in the United Kingdom by amaBooks Publishers and Carnelian Heart Publishing Ltd, The Mad takes us on a roller coaster kombi ride from Bindura to Harare, to Zengeza and to Chitungwiza Seke Units K and D, to kumusha in Shamva, to Mt Darwin and back to Harare. The protagonist, Hamundigone, is a mentally scarred former freedom fighter, who wanders through society criticising social injustices. He considers himself ‘a profound thinker who speaks his mind’. Previously a gifted teacher whose students gained the required 15 points to enter university, his erratic behaviour gets him fired from his post. On a lengthy kombi ride, Hamundigone rants at length to his fellow passengers about finding himself penniless and without resources on the streets of Harare. He devours a half-eaten burger from a bin outside a takeaway in Inez Terrace, and is beaten up by street kids who claimed ownership of all the scraps to be found in the bin. Rescued by some passing policemen, he spends the night at the charge office.

The kombi becomes a microcosm encompassing the post-independence ills of society. Hamundigone’s fellow passengers listen intently, half-afraid to interrupt his diatribe, but also curious to hear the end of his story.

Dr Mabasa bases many of his characters on people he has known, some of them mentally disturbed. Using madness as a device to give artistic freedom, he paints a picture of life for many Zimbabweans, that, 26 years later, seems little changed. A consummate sarungano, Mabasa was steeped in storytelling when growing up on his grandfather’s farm in Mount Darwin. Every evening he and his siblings would gather around the fire, mesmerised while his grandmother recounted ancient myths such as the River God Nyami Nyami, and traditional stories featuring animal tricksters like Tsuro (the Hare). ‘Story telling as an institution died with the liberation war’, said Mabasa. ‘Curfews were imposed, and by 5 pm no movement was allowed, and no fires could be lit’.

Readers will find the narrative of The Mad disjointed and sometimes confusing. This mirrors the state of mind of Hamundigone, who connects in unsettling ways at various times with all the other characters. In spite of his dishevelled appearance and unfiltered pronouncements, he often speaks the words of common sense. Distinguishing between right and wrong, his condition makes him unafraid to verbalise his opinions.

There are numerous sgebengas in The Mad, notably Vincent, aka VC, who makes money selling dagga, ‘a good grade, the best from Malawi’. He works from home, storing his contraband in the room he rents from his landlady, Mai Jazz. Business is good, and because he can pay his rent three months in advance, Mai Jazz refers to him as her ‘senior lodger’. In the narrative he’s described as ‘one of the indigenous businessmen that Bob and his government are talking about’.

Bunny, who was born kumusha and grew up herding cattle, came to Harare to start school. Qualifying as an auditor, he is one of the few stand-up characters in the story, always willing to assist others when they’re in dire straits. Moving from cramped quarters in Glen Norah, he rents a larger room in Zengeza 3, where his landlady is Maud, Hamundigone’s sister. Mabasa has a natural ear for dialogue, and the conversation when Maud, dressed in a slinky black dress, walks unannounced into Bunny’s room, is nothing short of a masterclass in seduction. Although Bunny already has a fiancée, and had planned to spend the evening quietly reading The Herald and cooking a meal of sadza in his kitchen/living room, the evening ends differently. Bunny falls in love with Maud, and is devastated when she dies of AIDS.

Of the many wild and wonderful characters in The Mad, one who stands out is Salisbury, the dog, whose name is changed to Harare after independence. Mai Jazz (previously a domestic worker in the suburbs, and known as Jerina) was given Harare by her white employers ‘when they took the gap and returned home to Britain’. The pedigreed pooch, once shampooed and brushed by Jerina, has to adapt to life in ‘the ghetto in Seke, Unit D’. Mai Jazz cashes in the money left to buy food for him at the pet shop in Newlands, and Harare has to learn to live by his wits, ‘eating dusty sadza and feeding from bins’.

Dr Mabasa has vivid memories of the random pieces of cloth his grandmother used to stitch together to make beautiful patchwork quilts. The Mad is structured in a similar way, the disjointed chapters illustrating an existence that for so many has become a nightmare. While there is no happy ending, and the story tells us to learn to be happy in our poverty, we are all the richer for the penetrative insights and experiences this important novel can give us.