THE southern African region is facing a serious energy crisis that could be detrimental to its industrialisation agenda.

Despite concerted efforts by relevant authorities in their respective jurisdictions to mitigate the situation, evidence on the ground indicates a prolonged power problem that needs massive capital to renew and increase the generation capacity of the vastly aged electricity infrastructure.

And due to the absence of long-term and affordable capital, industry bears the brunt.

South Africa (SA)’s power generation has deteriorated to the point where the continent’s most developed economy must deal with rolling power outages lasting up to 10 hours per day.

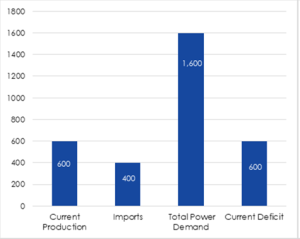

In Zimbabwe, the daily power supply deficit is over 900 megawatts during peak hours and to meet this deficit, Zesa is importing power from Zesco of Zambia, Eskom from South Africa, EDM and HCB of Mozambique.

Zambia had to implement a 12-hour electricity load-shedding programme until recently, which was subsequently reduced to eight hours per day.

Zimbabwe, on the other hand, has had to contend with up to 18 hours of load shedding, as demand has risen far above available supply. Power generation is averaging 885 megawatts (MW), against the current peak demand of 1 850MW.

In the country, the state power utility, Zesa Holdings, says the challenge may persist until at least 2025, as aggregate demand for energy has continued to surge.

The power cuts have had an adverse impact on industry, which is also battling to recapitalise and acquire modern technologies, with average industrial capacity estimated at around 66 percent.

The Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI) says due to power cuts, the cost of production has shot through the roof, with most producers running on diesel-powered generator sets that require significant foreign currency outlay.

It further states that load-shedding has cost businesses an average 30 percent of their output time.

“Capacity utilisation in the sector has dropped as most businesses cannot operate on usual number of shifts due to power cuts, this means that productivity no longer matches fixed costs of running plant and machinery. Significant time is lost when there is no power during daytime. This also takes into consideration the fact that generators cannot be run continuously without rest,” CZI said in a recent market update.

Analysts say reliable, affordable, and sustainable energy is a vital cog in the industrialisation agenda.

“The power crisis is very serious and affects most countries in the region. Zambia and Mozambique have a surplus, but the rest are all short of power. It’s difficult to estimate the impact, but SA estimates the losses at a billion rand a day,” economist Eddie Cross said.

“Energy is the driving force of the industrial world. Without it, you simply cannot develop and what is essential is availability —followed by affordability.”

The government says the resuscitation of the manufacturing sector has remained one of the key priorities, but captains of industry say authorities are not doing enough to secure long-term funding and implement policies that revive industry.

Gift Mugano

Industry has warned that downside risks that continue to exist, such as erratic power supply, supply chain disruptions, exchange rate depreciation, and a lack of modern equipment and machinery, could render the sector uncompetitive in the region in 2023.

Market watchers say exploitation of the potential of untapped energy resources’ potential is important in the context of industrial productivity and competitiveness.

Gift Mugano, an economist, said the energy crisis has raised the cost of doing business, negatively impacting the industrialisation agenda.

“The impact of power cuts has been massive. The major issue has been production, and that might have a major disruption on the supply chain because when you are out of power for a couple of hours, what it means is that you are out of production,” Mugano said.

“We can talk of alternative sources, including generators, but there are some industries that cannot be powered by generators in a competitive manner.

“The cost of production has been increased because, for those who rely on generators, the price of fuel has been skyrocketing due to the Russia-Ukraine war and the level it is now is uncompetitive. Energy is the blood in the industrialisation process and no doubt reliable and affordable energy is essential in the process.

“At the very port of call, we need to deal with the traditional mainstream energy, which is friendly. We need to restore the mainstream power source, which is hydroelectric.

“There is need to invest in hydroelectric power because we have lots of water in Africa — we can even have small hydropower stations. Maintenance and repairs need to be done because some of the issues affecting us now are because we are not up to date with maintenance,” Mugano added.

Recently, the Sadc Council of Ministers met in the Democratic Republic of Congo capital, Kinshasa, to look at priority regional development programmes to end the energy crisis.

“We want to move away from a concept where a country develops power, for example, the big INGA project in the DRC can be used to the benefit of the whole region and ensure adequate infrastructure to allow trade,” executive director of the Southern African Power Pool, Stephen Dihwa, said.

“We want to move away from a concept where a country develops power, for example, the big INGA project in the DRC can be used to the benefit of the whole region and ensure adequate infrastructure to allow trade,” executive director of the Southern African Power Pool, Stephen Dihwa, said.

“We are running a regional power electricity market where energy is traded on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis. We believe that once we do this, the load-shedding will come to an end.”

Eddie Cross Cross is a former member of Parliament and a member of the RBZ’s Monetary Policy Committee.

The provision of reliable and sustainable energy continues to be a priority for the southern Africa development agenda.

An inefficient energy supply is one of the biggest barriers to the development of a diversified, innovative and globally competitive base at a time the Sadc industrialisation strategy and roadmap — which runs from 2015 to 2026 — seeks economic liberation in the region.

The strategy is anchored on three pillars, namely industrialisation, competitiveness and regional integration.

The roadmap forecasts an increase in manufactured exports to at least 50 percent of total exports in the Sadc by 2030, from less than 20 percent at present, and to build market share in the global market for the export of intermediate products to East Asian levels of around 60 percent of total manufactured exports.

The roadmap also foresees the lifting of the regional growth rate of real GDP from four percent annually (since 2000) to a minimum of seven percent a year.

It also seeks to double the share of manufacturing value added in GDP to 30 percent by 2030 and to 40 percent by 2050, including the share of industry-related services, and to increase the share of medium-and-high-technology production in total manufacturing value added from less than 15 percent at present to 30 percent by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050.

newsdesk@fingaz.co.zw