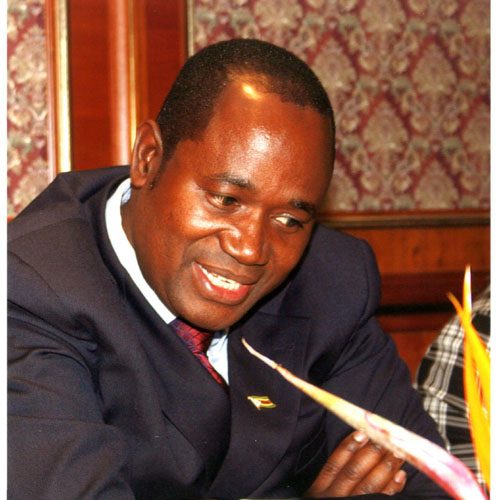

FORMER Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) governor Gideon Gono has responded to a Constitutional case in which he is accused by a former advisor Munyaradzi Kereke of corruption and misconduct, saying the application against him and the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) was “short on the law but long on heat, malice and verbiage”.

FORMER Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) governor Gideon Gono has responded to a Constitutional case in which he is accused by a former advisor Munyaradzi Kereke of corruption and misconduct, saying the application against him and the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) was “short on the law but long on heat, malice and verbiage”.

In a voluminous Heads of Argument filed with the Constitutional Court this week, Gono sought dismissal of Kereke’s case, arguing that analysis of all the papers filed revealed that the application was “ill-conceived at law and ill-founded in fact” and that it was “simply part of the well-documented war of attrition being waged by the applicant against” him.“The point cannot be emphasised enough that the Constitutional Court is not a general court. It is a specialist court intended as a court of final instance in relation to constitutional matters. It is therefore not the forum for personal grudges or political scores. For that reason and for reasons argued elsewhere in these heads, this honourable court must show its disquiet through an order for punitive costs against the applicant,” Gono argued.

Kereke approached the Constitutional Court, established under Zimbabwe’s new Constitution, alleging that ZACC had failed to investigate his complaint of alleged acts of corruption and irregular conduct by Gono while he was governor of the RBZ.

Kereke alleged that ZACC failed to investigate the complaint against Gono in wilful violation of the Constitution.

He alleged that the acts of ZACC had denied him protection of the law and wants the Constitutional Court to direct the ZACC to commence, within 30 days, an investigation into his complaints against Gono.

But Gono charged that Kereke’s application was defective in several respects, key of which was his failure to cite the RBZ and ZACC, both of which were interested parties in the case.

Besides, he said, Kereke had approached the court to “seek an order that he himself finds untenable”.He said Kereke’s application should fail on the basis that the application was “procedurally and substantially fatally defective”; that purely on grounds of procedure, the application did not acquit itself properly in matters about how pleadings are prepared and drafted; and that the application called for scrutiny in respect of the objections in limine made by Gono “which go to the root of the instant matter”.

Gono then dealt with the alleged defects in detail, one of which was failure to cite relevant parties in the case.

“The present application must fail for failure to cite the correct party. The applicant, does to cite the Commission. The Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, and not its chairman is the constitutional body charged with, among other things, the investigation of acts or alleged acts of corruption. The chairman of the Commission is, however, not a legal persona for the purposes of Chapter 13, Part 1, of the Constitution,” averred Gono.

“The apparent conflation of the office of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission with that of the chairman of the Commission is thus fatal. The situation would have been different if the chairman had been cited nomine officio. In this case, the applicant however, purposely, if erroneously, cited the chairman of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission as the constitutional body charged with exposing and investigating corruption. That defect is incurable and fatal to the applicant’s case. The position that failure to cite the correct party in civil proceedings is fatal to the applicant’s case is well-entrenched in our jurisprudence, it need not be belaboured.”

Gono said Kereke’s application was defective for its failure to cite the RBZ, which he said was clearly an interested party within the meaning of the law.

“The central bank is a body corporate with independent legal persona, created in terms of Section 317 of the Constitution. It is an interested party in this matter for a number of reasons.

“To start with, the 2nd respondent, at all material times, was acting as its principal accounting officer with respect to all the allegations by the appellant in the application. Consequently, all the issues discussed in this matter relate to its business. As such, to the extent that the allegations by the applicant against the 2nd respondent are material to the present case, only the Bank could attest to the propriety or otherwise of the 2nd respondent’s conduct,” said Gono, who is the 2nd respondent in the case.

The first respondent is the chairman of ZACC.

Gono maintained: “And indeed, as the 2nd respondent contends, if there was any malfeasance on his part, the Bank would be the direct complainant, it being the prejudiced party. In this context, it is immaterial what position the 2nd respondent held in the bank. His position cannot be conflated with that of the central bank.”

“Moreover, the disclosure of some of the official documents in this case might require the bank’s consent. In the circumstances, the central bank clearly has a direct and substantial interest in the outcome of this case. Moreover, an order by this honourable court for the 1st respondent’s commission to investigate the 2nd respondent will directly affect the central bank, which invariably will be required to open or make available its books, official documents, personnel and premises to the commission. An order by this court in the manner sought will thus impose a legal obligation on the central bank — for its cooperation — without affording it a chance to he heard.”

Gono said the failure to cite the RBZ was “a defect fatal to (Kereke)’s cause”.

“For reasons argued above, it is submitted that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe clearly has a direct and substantial interest in this matter. The central bank would be prejudiced if the case were to proceed without it being heard. It is indeed inconceivable that the official business of such an important and strategic national institution should play out in the public arena while it watches from the side-lines. Failure to join it in these proceedings should therefore be fatal. In making this submission, the 2nd respondent would like to point out that the applicant had the opportunity to address this anomaly once the issue had been brought to his attention through the 2nd respondent’s answering affidavit but chose not to. His obstinacy therefore should not work against the direct and substantial interests of the central bank,” said Gono.

He also argued that objectively, the order sought by Kereke was “absurd on the logic of the applicant’s own case and would in any event be reviewable on the grounds of bias”.

“The applicant, assuming he had correctly cited the Anti-Corruption Commission seeks an order directing same to conduct investigations against the 2nd respondent. However, half the applicant’s founding affidavit contains allegations that the 2nd respondent allegedly corrupted the Commission.

“The allegations are so serious and unkind. Furthermore, they are persisted with, in the answering affidavit. In the face of these allegations, surely rules of natural justice will disallow the Commission from investigating the 2nd respondent.”

“The basis of natural justice, is that justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done. Put differently, this honourable court is being asked to give a determination, which any outsider, including the applicant himself, may actually take on review on the basis of bias,” he said.

He also said Kereke’s case should fail under the principle of avoidance.

“Contrary to the applicant’s forceful, if misguided, averments in his affidavits, not every matter that raises a constitutional issue shall be heard as a constitutional case,” said Gono, who also argued that Kereke had approached the Court without exhausting other judicial processes.

“Directly related to the foregoing, the application should fail because the applicant has not, as a matter of law, exhausted all available ordinary remedies before approaching the Constitutional Court.”

“An incident of the principle of avoidance, the doctrine of ripeness, bars a party from asserting a constitutional issue in criminal or civil proceedings where other non-constitutional remedies are available,” he said.

He alleged that Kereke’s case was motivated by malice.

“The evidence of subjective malice is clearly shown by the fact that the applicant goes to town in producing and making serious defamatory attacks against the 1st and 2nd respondents when it was totally unnecessarily to do so. If the complaint was that the Anti-Corruption Commission had not investigated, then that is the simple allegation that should have been made and then an order sought to compel. The applicant knew that this matter would attract public interest and went ahead to produce the massive body of evidence he has produced in casu all in order to tarnish the image of the respondents,” he said.

newsdesk@fingaz.co.zw