Book review by DC Rodrigues

‘Whatever Happened to Rick Astley’

by Bryony Rheam

Parthian 214 pp., ISBN 978-1-77931-095-8

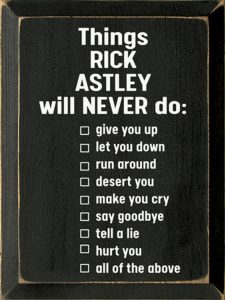

WHAT’S not to love about the rich baritone voice of Rick Astley, iconic English singer and pop sensation of the 80s? Fans of a certain age will remember ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’ and many other songs that were smash hits in England, Australia and America.

In 1994, after a string of hits, he disappeared from the scene, and in his own words, ‘slipped out the back door when no one was looking and no one cared’. But some people did seem to care, and it was his disappearance that inspired the title of Bryony Rheam’s recently published collection of sixteen short stories, ‘Whatever Happened to Rick Astley?’

Set in Bulawayo, Lusaka, London and Bristol, Rheam explores a number of themes and familiar situations that will resonate on many levels and in different ways with readers all over the world. In ‘Potholes’ an admirable character, Gibson Sibanda, takes it upon himself to traverse the suburbs of Bulawayo, filling potholes with sand and small stones.

Grateful motorists sometimes stop to reward him for his work. As an aside, when considering the number of potholes bedevilling the roads throughout Zimbabwe, the appointment of a dedicated Minister of Potholes might be considered a priority. Zimbabwe is not alone in this problem, and Jeremy Hunt, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the UK, has allocated GBP700 million every year to deal with ‘the curse of potholes’. The fictional Sibanda takes his work seriously, and although he suffers some heartbreaking setbacks, is not deterred from his mission to make the roads of Bulawayo safe.

Grateful motorists sometimes stop to reward him for his work. As an aside, when considering the number of potholes bedevilling the roads throughout Zimbabwe, the appointment of a dedicated Minister of Potholes might be considered a priority. Zimbabwe is not alone in this problem, and Jeremy Hunt, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the UK, has allocated GBP700 million every year to deal with ‘the curse of potholes’. The fictional Sibanda takes his work seriously, and although he suffers some heartbreaking setbacks, is not deterred from his mission to make the roads of Bulawayo safe.

The passage of time is a constant theme in Rheam’s stories. Says Prufrock, In TS Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock, ‘I have measured out my life in coffee spoons’. In ‘The Rhythm of Life’, seasons come and go, and husband and wife, ex-farmers from Headlands, take bets every year on which day in November the first rains will fall.

The passage of time is a constant theme in Rheam’s stories. Says Prufrock, In TS Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock, ‘I have measured out my life in coffee spoons’. In ‘The Rhythm of Life’, seasons come and go, and husband and wife, ex-farmers from Headlands, take bets every year on which day in November the first rains will fall.

St Joseph lilies are collected and arranged in vases every February, and sweet pea and poppy seeds are planted in April. August winds regularly bring the threat of veldt fires, to be extinguished by buckets of water, kept at the ready. Anticipating these events creates what Rheam refers to as ‘the soft, undulating rhythm of life’, relied upon to provide ‘our sense of security and continuity.’ A new theme is introduced when the couple leave Zimbabwe, emigrating to an unnamed country where ‘the long journey to work’ is in ‘an overfilled railway carriage’.

People have been emigrating for centuries, settling with varying degrees of success in their adopted country. Fossils found in the Cradle of Mankind outside Johannesburg, show that humans left their African homeland 80,000 years ago to colonise the world. While oppression, social marginalisation, or a desire to follow family members to other parts of the world may prompt migration, it’s safe to assume that some of Rheam’s characters abandon their social networks and culture for economic reasons.

William Lloyd, in ‘Last Drink at the Bar’, imagines ‘old age, senility and death’ in Zimbabwe, and ‘as much as he loved Bullies’ (Bulawayo), decides to obtain an ancestry visa and trace his father’s roots back to Cardiff in Wales. Failing to find a bar to his taste in Cardiff, or any drinking mates to replace Frikkie, Leonard and Rookie, he eventually finds himself again at Gatwick airport, this time heading north to a new life in Scotland.

Although Bryony Rheam is a young woman with a young family, she seems to understand the plight of many of her characters, who are elderly and widowed, struggling with a lack of money, and are separated from their children who have emigrated to the UK or to Australia.

There have been several waves of emigration from Zimbabwe, starting in 1965 with the declaration of UDI in Rhodesia; but it is the socio-political crisis that began in 2000 that has seen the number of Zimbabweans inhabiting the diaspora swell to over five million. The effect of this second wave of emigration provides the backdrop to this anthology, allowing Rheam to describe with skill and empathy through fiction, the lives of those who fled abroad and those who stayed behind.

Alternately referred to as ‘she’ or ‘Mom’, the narrator of the final story in the collection reminisces about ‘the good old days’ and imagines attending a Rick Astley concert with her boyfriend, Victor. Searching on Google she discovers that the pop icon of the 80s has come out of retirement, wowing thousands of fans at the Pyramid stage at Glastonbury earlier this year. Relieved that all is well with Rick Astley, ‘Mom’ now feels reassured and positive about her own role in life.

Through her characters, Bryony Rheam explores the themes of parenthood, ageing, lack of money, time past and time present, and immigration. Dispiriting as some of the stories may seem, her fictional characters are compelling and familiar; they also reflect a specific time in the history of Zimbabwe, and will provide compulsive reading for future generations .