Something is always up in the world of the arts in Bulawayo.  Picture this : there is the nice little coffee shop by the National Gallery in the garden and the morning sun with its lilting streaks of light adding ambience to the scene. It is the stuff that leisure is made of. Or is it? Art is the reason why we have all the things we take for granted. A house is a work of art as much as the chair I am sitting on as I write. What indeed is not art?

Picture this : there is the nice little coffee shop by the National Gallery in the garden and the morning sun with its lilting streaks of light adding ambience to the scene. It is the stuff that leisure is made of. Or is it? Art is the reason why we have all the things we take for granted. A house is a work of art as much as the chair I am sitting on as I write. What indeed is not art?

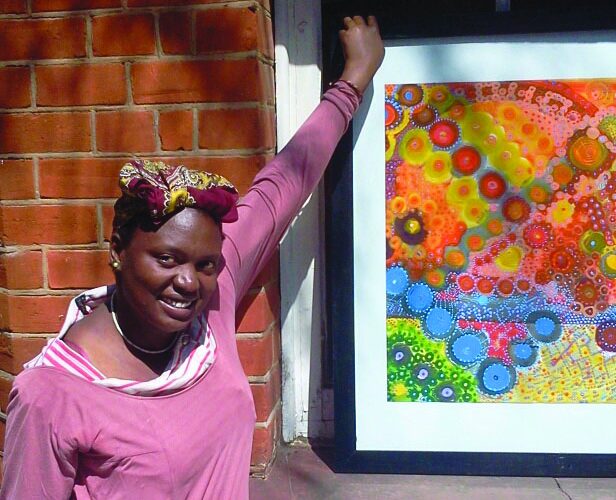

This week I had the privilege of sitting down for coffee and have a conversation with quite possibly one of the most important new young artists of her generation alongside Owen Maseko and Shamilla Asha — all celebrated visual artists who haunt the National Gallery. My job is to bring them home to you and debunk the misconception around artists, why they do what they do, what it is that they do, when did they start doing it and what else they do, if at all. These are questions I pose to my subjects who are indeed my muses. So it’s not simple reportage. It is something which is a cross between an inquisition, exploration and ultimately a portrait captured through the prism of my own biases and personal goals. Why would I bother writing any way? So, 30-year old Zandile Masuku, a BA (hons) Architecture graduate and solo artist in her maiden exhibition held last week at the National Gallery in Bulawayo is a worthwhile subject precisely because she is articulate, thoughtful and highly creative. She writes poetry, paints and her day job is as an architectural coordinator at a construction company. Working with the boys and battling to chart her way through the boys club. But that designation is misleading. It does not adequately describe the fact that she is a polymath, people like Leonardo Da Vinci who are gifted in many things. At least that is her plan.

What sort of things fertilised your imagination growing up?

I read The long walk to freedom by Nelson Mandela when I was 14 years old in my parents’ library and it blew my mind. I decided at 17 to be an architect. My step dad has been my chief supporter and I read books from his library. I liked reading as a child. I liked Maya Angelou, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Ernest Hemingway. I was surrounded by books. My mom is a farmer and my dad is a cardiologist. There were books at home. As a trainee architect, Zandile Masuku is on the way to achieving her polymath goal. But it’s a man’s world. That is how James Brown saw the world in his famous hit song. Yet he added that it would be nothing without a woman or girl. That is how she describes the world of architecture especially in Bulawayo.

How was your first foray into field?

I clashed a lot with the guys mainly trained at N.U.S.T. What the hell does she think she is? Coming here telling us what to do.

Are you an artist who is not worried about rent?

Not at the moment. Because the house I live in is my parents’ home.

I once asked this question to the late Dr Yvonne Vera (celebrated late author and former National Art Gallery director). And she said that she could afford to travel and do the things that she wanted to do. What of you Zandile ?

(interjecting) Owen Maseko: But that takes a long time.

Zandile Masuku: I once met her when I was in varsity (Brighton University U.K.) She was a remarkable woman and she actually gave me the gift of writing pads and told me to just write and write anything.

Why do you do what you do? When did you start doing what you do? What is it that you do? Are there other things that you do?

Professionally I am a budding artist and the realisation or the calling came late last year in November. I went to the U.K. when I was nineteen. I managed to get a job to work directly with a developer as an architectural coordinator in a construction. But my degree is in architecture. I do a bit of planning and a bit of project planning. It is my first job in construction. After I finished university, I moved from Brighton (the south coast of England) and went to London before deciding to come back in 2009. While I was here in 2010 I discovered I was pregnant with my son and decided to put that (construction job) on hold whilst my son was growing. I did teach swimming for two years at the Jewish private school Carmel Primary. Last year I switched from teaching to construction. As far as painting and poetry is concerned it occurred intermittently whenever the pressure got to me even in varsity. I would paint and write poetry for two years and got into spoken word. I call myself an artist/designer/architect. Its four years inside university and three years’ work experience before I am a fully-certified architect under the British system. I am on my way there. It is very difficult for me trying to break into architecture and there is a nice little boys club. I was still trying to decide whether architecture was still the thing for me late last year though. For me to survive I have to switch on my masculine traits to survive. I am not free to talk about my work because of confidentiality. But when I went to work there it was 10 guys and one female.

What’s this exhibition about?

The theme of my exhibition is about hybridism. In December I was awarded best female artist and that is the thing that got me into the gallery and hence this exhibition “DOT.CONNECTED”.

Why did you call the exhibition “DOT.CONNECTED”?

I am 30 years old now and if at 30 you don’t know what you are all about then you are lost. Originally I wanted to call it Cycle of Life. Then I discovered that someone in New York was doing a similar named exhibition at the same time. The political borders are dissipating because of the internet. The political borders are just that. They are not real. I left when I was 19. You borrow an identity. You recreate yourself and in that process of adapting you become a new person. When I came back I realised that I am new person. That is how I came up with the idea of hybridisation. My Ndebele identity and this borrowed European identity. But it’s not unique to me. There are many Zimbabweans living abroad with different hybrid identities. You realise the value of your identity and your difference from other people. A lot of people have gone overseas and are coming back and having to deal with it. When you go somewhere and you become part of an ethnic minority you tend to confront that reality. I had to re-embrace that part of me. Coming into the gallery is a form of institutionalisation for me.

Did you ever try to underplay that aspect of yourself like some of the uppity young people from well to do families?

No. What happened was that I met a lot of Zimbabweans who were trying to identify themselves as South Africans.

Why do you think the Zimbos did that?

Because they were not proud of their Zimbabweanness. I thought I was not gonna do that. If anything I was going to be an ambassador of sorts.

How is your work related to everyday Joe ?

I am not necessarily trying to relate to people. Each piece is a snapshot of a moment. Elements of my Ndebeleness and borrowed European identity. Themes of gender, the cosmos, climate change, spirituality. I would like my art to invite people to engage with things they are not consciously aware of. For example climate change.

The Maldives is a country that is one and half metres above sea level. In a few years time, it will disappear due to global climate change. My role is to open up people’s minds. The plan is move from the visual world and move into graphic designer. I want to see my painting on t-shirts or garments for example.